Hidden pornographic poems explain 'bestseller' success of C18 poetical volumes

An Oxford University academic has explained the secret behind the success of two of the best selling volumes of poetic miscellanies in the 18th Century – a series of pornographic poems were hidden at the back of the book.

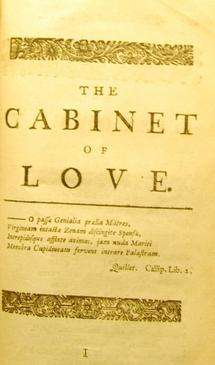

Dr. Claudine van Hensbergen of the English Faculty came across ‘The Cabinet of Love’ in two volumes of The Works of the Earls of Rochester and Roscommon while cataloguing poetic miscellanies for Oxford University’s Digital Miscellanies Index project, funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

Although the existence of The Cabinet is already known about, Dr. van Hensbergen is the first to attribute the success of The Works – which was reprinted more than 20 times in the 18th Century – to the dirty ditties, whose location would initially have been spread by word of mouth.

The finding suggests that what we think of as high art and low art was being packaged, sold and read together in the 18th Century – and raises questions about whether the popularity of other bestselling books might have different explanations.

Dr. van Hensbergen said: "I had just finished entering details of poems typical of miscellanies of the period- satires, imitations and amatory verse, when at the end of the second volume a new title page announced the start of ‘The Cabinet of Love’.

"To my surprise, ‘The Cabinet’ turned out to be a collection of pornographic verse about dildos. The poems include ‘Dildoides’, a poem attributed to Samuel Butler about the public burning of French-imported dildos, ‘The Delights of Venus’, a poem in which a married woman gives her younger friend an explicit account of the joys of sex, and ‘The Discovery’, a poem about a man watching a woman in bed while hiding under a table.

"In later years, a celebratory poem about condoms was added, as well as several obscene botanically themed verses attributed to ‘a Member of a Society of Gardeners’ in which male genitalia is described as the ‘tree of life’."

Dr. van Hensbergen said: ‘I think the inclusion of ‘The Cabinet’ is key to understanding why this miscellany proved so popular for so long.

Although its existence is not made clear on the title page of The Works, word of it must have spread as in the later decades of the century ‘The Cabinet’ was properly integrated into the volume, and was even bound at least twice at the opening of volume two. We know pornographic writing was printed and sold in the period but it’s difficult to establish a complete record. In many cases all we have to go on are references to the titles of pornographic works rather than the books themselves.

The notorious printer Edmund Curll first inserted ‘The Cabinet’ into a 1714 edition of The Works, and it was reprinted more than twenty times throughout the century.

Dr. van Hensbergen said: "‘The Cabinet’ is unusual because it shows us that people read pornographic writing directly alongside the verse of major poets. This raises interesting questions about what counts as literature and where the boundaries between high and low culture lie. These ideas were much more fluid in the 18th century than they are today."

Samuel Pepys provides a good example of how, in some cases, pornographic works were read and then destroyed: an entry in Pepys’s diary for January 1668 reveals how on browsing in a London bookshop he picked up a copy of the French work, ‘L’Ecole des Filles’, thinking it would be a good book for improving his wife’s language skills. When he realized it was a pornographic work he left the shop, only to return later to buy himself a copy. In his diary he using the book before burning the book so that it wouldn’t be found in his library. Ironically, the survival of his diary has linked him to the work for posterity and serves as proof that this book found its way onto English shores.

Dr. van Hensbergen is preparing an article on “The Cabinet’, thinking about how its circulation alongside the works of the Earl of Rochester helped to cement a cultural link between Rochester and pornography. The original English libertine, Rochester produced a significant body of poetry, impressive for its biting satirical wit and scope of enquiry. Rochester famously employed obscene language and imagery in his work, but he did so to reveal the dark and uninviting side of human nature and society. His poems stand in opposition to pornographic writing – like that found in ‘The Cabinet’ – which ultimately seeks to arouse sexual desire. "Rochester continues to occupy an assured but ambivalent position in the literary canon as we still find it difficult to separate his reputation from his work," Dr. van Hensbergen explained.

Dr. Abigail Williams, the principal investigator of the Digital Miscellanies Index project said: "Finding ‘The Cabinet of Love’ is another great example of why the Digital Miscellanies Index project is so important, as it’s giving us a fuller picture of the poems being read in the 18th century, and the often surprising ways in which they were collected together. Miscellanies are an often overlooked resource that can tell us a lot about poetic taste in the period."

The team behind the Digital Miscellanies Index are working to create an online catalogue of the world’s largest collection of 18th century miscellanies, a body of works vital to understanding the diversity of 18th century literary culture. It is a three-year Research Project Grant funded by the Leverhulme Trust. The Works is held in Oxford University’s Bodleian Libraries, among other places.

Provided by Oxford University