Exceptional fossils reveal the earliest evidence of social behavior in mammals

Evidence of lifestyle and social behavior is almost never preserved in the fossil record. Now, a group of researchers from the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (Paris), CNRS (Paris) and Museo de Historia naturel Alcide d'Orbigny de Cochabamba (Bolivia) has excavated a remarkable collection of dozens of small mammal skulls and skeletons from the Tiupampa site in the central Andes in Bolivia that provides compelling fossil evidence of social behavior. A study of these remains, published this week in Nature, reveals the oldest example of group-living in mammals.

Today, many mammals live in groups. Others, such as most marsupials (which include the South American opossums and Australian koalas and wombats), are strictly solitary. We know very little about social behavior of fossil mammals, because only rarely is the number of preserved individuals large enough to provide evidence of community life.

Now, the discovery of a population of a mouse-sized ancient relative of marsupials (Pucadelphys andinus) from the early Tertiary (64 million years ago) in Bolivia demonstrates that group-living appeared early in the mammalian history, and may even represent the ancestral condition for mammals as a whole.

Exceptional preservation

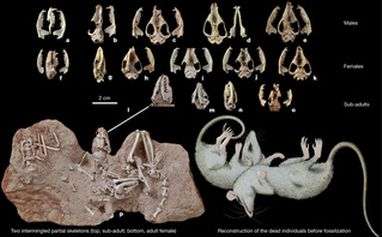

The vast majority of fossil mammals are known from isolated teeth, or, at best, fragments of jawbones. Skulls or skeletons are extremely rare and are usually damaged or incomplete. In this context, the discovery of intact skulls and skeletons representing 35 individuals of the ancient marsupial relative Pucadelphys andinus within an area of only a few square metres, constitutes a major event in our knowledge of mammalian history and the evolution of social behavior.

Social life and sexual dimorphism

This discovery provides evidence that, unlike living marsupials, marsupial relatives from the beginning of the Tertiary period lived in groups. In addition, the mouse-sized Pucadelphys exihibits strong sexual dimorphism, with the males having a larger and more robust skull and much larger canines than females.

Among the 22 best preserved skeletons and skulls, the scientists have been able to identify 6 males, 12 females and 4 sub-adults, for which sex is not determinable. The presence of such a large number of individuals in only a few of square metres, together with their marked sexual dimorphism, indicates that Pucadelphys lived in groups, with competition between males for females and a polygynous mating system (one male mates with more than one female). The climate of Bolivia 64 million years ago appears to have been tropical, and so Pucadelphys probably reproduced all year round, unlike the seasonal breeding behavior seen in mammals that live in temperate or cold climate regions.

The Tiupampa population of Pucadelphys lived on the banks of a big tropical river and was most probably engulfed by a sudden flash flood. We know that these animals were fossilized on the spot because their remains are too well preserved to have been transported. Thus, these 35 individuals lived and died together in a single group, 64 million years ago.

The Bolivian fossils provide us with the earliest evidence of group-living in mammals and reveal a previously unknown part of their social behavior at the very beginning of the Tertiary period – the so-called “Age of mammals”.

More information: Sandrine Ladevèze, et al. Earliest evidence of mammalian social behaviour in the basal Tertiary of Bolivia. DOI: 10.1038/nature09987 , Nature, 8 mai 2011.

Abstract

The vast majority of Mesozoic and early Cenozoic metatherian mammals (extinct relatives of modern marsupials) are known only from partial jaws or isolated teeth, which give insight into their probable diets and phylogenetic relationships but little else. The few skulls known are generally crushed, incomplete or both1, 2, 3, 4, and associated postcranial material is extremely rare. Here we report the discovery of an exceptionally large number of almost undistorted, nearly complete skulls and skeletons of a stem-metatherian, Pucadelphys andinus, in the early Palaeocene epoch5 of Tiupampa in Bolivia6, 7, 8. These give an unprecedented glimpse into early metatherian morphology, evolutionary relationships and, especially, ecology. The remains of 35 individuals have been collected, with 22 of these represented by nearly complete skulls and associated postcrania. These individuals were probably buried in a single catastrophic event, and so almost certainly belong to the same population9. The preservation of multiple adult, sub-adult and juvenile individuals in close proximity (<1 m2) is indicative of gregarious social behaviour or at least a high degree of social tolerance and frequent interaction. Such behaviour is unknown in living didelphids, which are highly solitary and have been regarded, perhaps wrongly, as the most generalized living marsupials. The Tiupampan P. andinus population also exhibits strong sexual dimorphism, which, in combination with gregariousness, suggests strong male–male competition and polygyny. Our study shows that social interactions occurred in metatherians as early as the basal Palaeocene and that solitary behaviour may not be plesiomorphic for Metatheria as a whole.

Provided by CNRS