How cells know when to tighten the belt

The epithelial cells that line the surface of tissues form a tightly sealed barrier, with individual cells joined together by structures called apical junctional complexes (AJCs). However, embryonic epithelium undergoes multiple physical rearrangements over development. For example, early in the formation of the brain and spinal cord, a subset of epithelial cells fold inward to form a groove that ultimately develops into a ‘neural tube’.

Such changes are achieved through the physical constriction of the apical (upper) domains of selected epithelial cells, a process driven by a ring-shaped network of cables composed of actin and myosin protein that are anchored at the AJCs. Now, work from Masatoshi Takeichi and postdoctoral fellow Takashi Ishiuchi of the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Kobe has revealed an unexpected role for a protein named Willin in regulating this constriction1.

Willin was previously assumed to act primarily as the mammalian equivalent of Expanded, a fruit fly protein that regulates growth. “It turned out that Willin localizes along cell junctions,” says Takeichi, “and we got interested in what it was doing there.”

They determined that Willin associates with a pair of proteins—Par3 and atypical protein kinase C (aPKC)—that help epithelial cells maintain their polarity, with clearly defined apical (top) and basal (bottom) segments. Willin and Par3 both seem to execute highly similar functions: they bind to and shepherd aPKC to AJCs, where aPKC acts to inhibit actomyosin-mediated constriction.

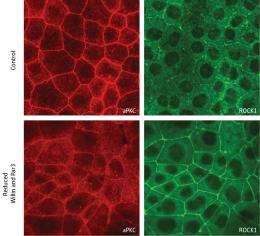

Since aPKC is an enzyme that regulates the function of other proteins by tagging them with chemical modifications, Takeichi and Ishiuchi searched for potential targets. Proteins known as Rho-associated kinases (ROCKs) localize to AJCs and modulate the function of actomyosin fibers, and the researchers confirmed that the ROCKs are direct targets of aPKC. The presence of unmodified ROCK at AJCs appears to promote apical constriction; however, after delivery of aPKC to the AJC, it inhibits constriction by modifying ROCK and triggering its release into the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). “This was really an unexpected discovery,” says Takeichi.

These results show that Willin is an important regulator of epithelial cell shape, but Takeichi is not ready to discard the possibility that it may still perform functions that echo those of its cousin, Expanded. “Growth control and junctional contraction might be physiologically linked,” suggests Takeichi. “A future goal would be to clarify whether vertebrate Willin is involved in growth control and, if so, how this relates to its ability to induce epithelial apical constriction.”

More information: Ishiuchi, T. & Takeichi, M. Willin and Par3 cooperatively regulate epithelial apical constriction through aPKC-mediated ROCK phosphorylation. Nature Cell Biology 13, 860–866 (2011).

Provided by RIKEN