Discovery of facial malformation gene

(PhysOrg.com) -- The first specific genetic mutation which can cause a potentially serious facial disfigurement has been identified by researchers at Oxford University. The finding, published online in the American Journal of Human Genetics, offers the promise of improved genetic counselling for parents at risk.

Formation of the human face is a complex and exquisitely orchestrated developmental process that occurs between four and eight weeks of embryonic development. Disturbance to this development can lead to malformations of the head and face, including abnormal nasal configuration, cleft lip, and widely spaced eyes.

Most cases of disfigurement are caused by damage to the developing embryo early in pregnancy; genetic causes are thought to be responsible for only a minority of cases, and these usually also involve other parts of the body. No mutation of a single gene has previously been identified that leads specifically to facial malformations.

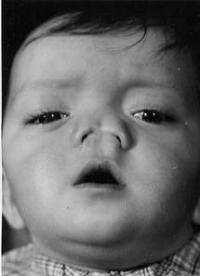

Researchers, led by Professor Andrew Wilkie from the Weatherall Institute for Molecular Medicine at the University of Oxford and Dr Irene Mathijssen from the Erasmus Medical Centre in the Netherlands and funded by the Wellcome Trust, identified individuals from seven families who shared a similar, distinctive facial appearance, including an abnormally large distance between the eyes and a wide, malformed nose. They termed this condition ‘frontorhiny’.

Genetic analysis showed that each of the individuals carried two copies of a mutation in the gene ALX3. Mouse models have previously highlighted the involvement of the equivalent gene in the production of a protein which regulates other genes involved in facial development - in other words, switching them on and off. However, while the absence of the protein produced by this gene does not disrupt facial development in mice, Professor Wilkie and colleagues found that in humans it leads to frontorhiny.

‘Frontorhiny can be a very distressing condition,’ says Professor Wilkie. ‘It causes facial disfigurement and other health problems, such as breathing difficulties and dermoids (benign cysts under the skin). The cosmetic surgery can be very challenging, requiring multiple operations.’

By identifying and naming the condition, the researchers believe that they will be able to diagnose more cases and provide improved genetic counselling. Because this is a recessive genetic disorder, a parent with the condition is very unlikely to have a similarly affected child. However, where unaffected parents have a child with the condition, they have a one in four chance of each future child being affected.

‘This finding is very important from the point of view of genetic counselling and offers hope to those families considered to be at risk,’ explains Professor Wilkie. ‘For example, by correctly diagnosing the condition in an adult, we can reassure them that their children are unlikely be affected.’

Professor Wilkie believes that the research also highlights the power of genetics to identify the origins of genetic disorders.

‘This study illustrates the tremendous power of genetics to identify the origins of rare disorders such as frontorhiny, even when working with very small numbers of individuals. In this research, just three affected individuals helped us to narrow the search for the particular genetic mutation responsible to around one three thousandth of the human genome. The previous mouse genetic work then helped finish the job for us.’

Provided by Oxford University (news : web)