Japanese scientists aim to create robot-insects

Police release a swarm of robot-moths to sniff out a distant drug stash. Rescue robot-bees dodge through earthquake rubble to find survivors.

These may sound like science-fiction scenarios, but they are the visions of Japanese scientists who hope to understand and then rebuild the brains of insects and programme them for specific tasks.

Ryohei Kanzaki, a professor at Tokyo University's Research Centre for Advanced Science and Technology, has studied insect brains for three decades and become a pioneer in the field of insect-machine hybrids.

His original and ultimate goal is to understand human brains and restore connections damaged by diseases and accidents -- but to get there he has taken a very close look at insects' "micro-brains".

The human brain has about 100 billion neurons, or nerve cells, that transmit signals and prompt the body to react to stimuli. Insects have far fewer, about 100,000 inside the two-millimetre-wide (0.08 inch) brain of a silkmoth.

But size isn't everything, as Kanzaki points out.

Insects' tiny brains can control complex aerobatics such as catching another bug while flying, proof that they are "an excellent bundle of software" finely honed by hundreds of millions of years of evolution, he said.

For example, male silkmoths can track down females from more than a kilometre (half a mile) away by sensing their odour, or pheromone.

Kanzaki hopes to artificially recreate insect brains.

"Supposing a brain is a jigsaw-puzzle picture, we would be able to reproduce the whole picture if we knew how each piece is shaped and where it should go," he told AFP.

"It will be possible to recreate an insect brain with electronic circuits in the future. This would lead to controlling a real brain by modifying its circuits," he said.

Kanzaki's team has already made some progress on this front.

In an example of 'rewriting' insect brain circuits, Kanzaki's team has succeeded in genetically modifying a male silkmoth so that it reacts to light instead of odour, or to the odour of a different kind of moth.

Such modifications could pave the way to creating a robo-bug which could in future sense illegal drugs several kilometres away, as well as landmines, people buried under rubble, or toxic gas, the professor said.

All this may appear very futuristic -- but then so do the insect-robot hybrid machines the team has been working on since the 1990s.

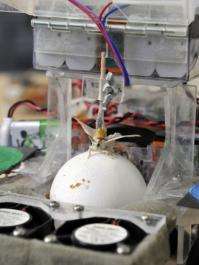

In one experiment, a live male moth is strapped onto what looks like a battery-driven toy car, its back glued securely to the frame while its legs move across a free-spinning ball.

Researchers motivate the insect to turn left or right by using female odour.

The team found that the moth can steer the car and quickly adapt to changes in the way the vehicle operates -- for example by introducing a steering bias to the left or right similar to the effect of a flat tyre.

In another, more advanced, test, the team severed a moth's head and mounted it onto the front of a similar vehicle.

They then directed similar odour stimuli to the contraption which the insect's still-functioning antennae and brain picked up.

Researchers recorded the motor commands issued by nerve cells in the brain, which were transmitted to steer the vehicle in real time.

The researchers also observed which neuron responds to which stimulus, making them visible using fluorescent markers and 3-D imaging.

The team has so far obtained data on 1,200 neurons, one of the world's best collections on a single species.

Kanzaki said that animals, like humans, are proving to be highly adaptable to changing conditions and environments.

"Humans walk only at some five kilometres per hour but can drive a car that travels at 100 kilometres per hour. It's amazing that we can accelerate, brake and avoid obstacles in what originally seem like impossible conditions," he said.

"Our brain turns the car into an extension of our body," he said, adding that "an insect brain may be able to drive a car like we can. I think they have the potential.

"It isn't interesting to make a robo-worm that crawls as slowly as the real one. We want to design a machine which is far more powerful than the living body."

(c) 2009 AFP