Scientists Discover Hunger's Timekeeper

(PhysOrg.com) -- Researchers at Columbia and Rockefeller Universities have identified cells in the stomach that regulate the release of a hormone associated with appetite. The group is the first to show that these cells, which release a hormone called ghrelin, are controlled by a circadian clock that is set by mealtime patterns. The finding, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has implications for the treatment of obesity and is a landmark in the decades-long search for the timekeepers of hunger.

The scientists, led by Rae Silver, head of Columbia’s Laboratory of Neurobiology and Behavior and Helene L. and Mark N. Kaplan Professor at Barnard College, showed that ghrelin’s release whets the appetite of mice, spurring them to actively search for and consume food, even when they are not hungry. In addition to Silver, the researchers involved in the study include Barnard College senior research scientist Joseph LeSauter and collaborator Donald Pfaff at The Rockefeller University.

“Circadian clocks allow animals to anticipate daily events rather than just react to them,” said LeSauter, who ran and supervised the study’s experiments. “The cells that produce ghrelin have circadian clocks that presumably synchronize the anticipation of food with metabolic cycles.”

Previous studies have shown that people given ghrelin injections feel voraciously hungry and eat more at a buffet than they otherwise would. The new research suggests that the stomach tells the brain when to eat and that establishing a regular schedule of meals will regulate the stomach’s release of ghrelin. “If you eat all the time, ghrelin secretion will not be well controlled,” said Silver, the paper’s lead author and the principal investigator of the study. “It’s a good thing to eat meals at a regularly scheduled time of day.”

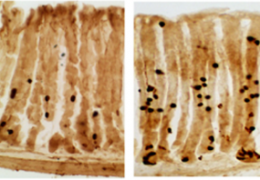

The scientists show that stomach cells in mice release ghrelin into the general circulation before meal time. The hormone triggers a flurry of food seeking behavior associated with hunger and stimulates eating.

LeSauter studied genetically engineered mice lacking the receptor that recognizes ghrelin and compared them with normal mice on identical feeding schedules. He found that the mice that lack the ghrelin receptor began to forage for food much later and to a lesser extent than their normal counterparts.

Pfaff believes that ghrelin, which travels from the stomach through the bloodstream to the brain, influences a decision-making process in brain cells. These brain cells are constantly deciding whether or not to eat, and as mealtime draws near, the presence of ghrelin increases the proportion of “yes” decisions.

The research underscores that ghrelin, the only known natural appetite stimulant made outside the brain, is a promising target for drug developers. Unlike drugs that focus on satiety, those that target ghrelin could help curb appetite before dieters take their first bite.

Provided by The Earth Institute at Columbia University (news : web)