February 18, 2010 feature

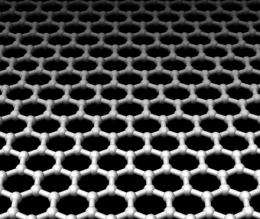

Can graphene nanoribbons replace silicon?

(PhysOrg.com) -- "Graphene has been the subject of intense focus and research for a few years now," Philip Kim tells PhysOrg.com. "There are researchers that feel that it is possible that graphene could replace silicon as a semiconductor in electronics."

Kim is a scientist at Columbia University in New York City. He has been working with Melinda Han and Juliana Brant to try and come up with a way to make graphene a feasible replacement for silicon. Toward that end, they have been looking at ways to overcome some of the problems associated with using graphene as a semiconductor in electronic devices. They set forth some ideas for electron transport for graphene in Physical Review Letters: “Electron Transport in Disordered Graphene Nanoribbons."

“Graphene has high mobility, and less scattering than silicon. Theoretically, it is possible to make smaller structures that are more stable at the nanolevel than those made from silicon,” Kim says. He points out that as electronics continue to shrink in size, the interest in finding viable alternatives to silicon is likely to increase. Graphene is a good candidate because of the high electron mobility it offers, its stability on such a small scale, and the possibility that one could come up with different device concepts for electronics.

There are problems with graphene, though. “First of all, graphene does not have a band gap, and that is essential for semiconductor device operation,” Kim points out. “Previously, we found that you can create an energy gap by cutting graphene into strips, creating nanoribbons..” Of course, now that scientists can use nanoribbons to create an energy gap, a new set of challenges has arisen. “The gap is not so simple as we first thought. We have new complications to deal with now in the way the energy gap behaves.”

Kim and his colleagues discovered that the nanoribbons have a rough edge, creating more scattering than they would like. “There is good control up to the nanometer,” he says, “but the control is not as precise at the atomic level.” Another issue is that the nanoribbons sit on a substrate, adding more disorder. “Our paper here is mostly concerned with identifying these issues, so that we can better understand how graphene nanoribbons might be used in the future,” Kim insists. “We want to understand the nature of the energy gap so that we can perhaps engineer smoother atomic edges and create a better substrate that does not induce disorder potential.”

With the knowledge of how to create an energy gap with graphene nanoribbons available, and with some of the properties of the gap identified, it is possible to begin making changes. “I’m hopeful that in the future we might be able to use graphene to compete with silicon,” Kim says. “The high mobility of graphene makes it a good candidate, and since it is likely to be more stable at the nanoscale, there is real potential. However, we need to be able solve some of these other problems first. But we are well on our way.”

More information: Melinda Han, Juliana Brant, and Philip Kim, “Electron Transport in Disordered Graphene Nanoribbons,” Physical Review Letters (2010). Available online: link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.056801 .

Copyright 2010 PhysOrg.com.

All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of PhysOrg.com.