A Little Less Force: Making Atomic Force Microscopy Work for Cells

(PhysOrg.com) -- Scientists with Berkeley Lab?s Molecular Foundry have developed a nanowire-based imaging technique by which atomic force microscopy could be used to study biological cells and other soft materials in their natural, liquid environment without tearing apart or deforming the samples. This could provide scientists with the long coveted non-destructive means of dynamically probing soft matter.

Atomic force microscopy, a tactile-based probe technique, provides a three-dimensional nanoscale image of a material by gliding a needle-like arm across the material’s surface. The core of AFM imaging workhorse is a cantilever with a sharp tip that deflects as it encounters undulations across a surface. Due to a minimum force required for imaging, conventional AFM cantilevers can deform or even tear apart living cells and other biological materials. While scientists have made strides in reducing this minimum force by making smaller cantilevers, the force is still too great to image cells with high resolution. Indeed, for imaging objects smaller than the diffraction limit of light—that is, nanometer dimensions—this approach hits a roadblock as the instrument can no longer sense minute forces.

Now, however, scientists with the Molecular Foundry, a U.S. Department of Energy User Facility located at Berkeley Lab, have developed nano-sized cantilevers whose gentle touch could help discern the workings of living cells and other soft materials in their natural, liquid environment. Used in combination with a revolutionary detection mechanism, this new imaging tool is sensitive enough to investigate soft materials without the limitations present in other cantilevers.

“Whether we are considering biological systems or other complex, self-assembling nanostructures, this organization will be done in a liquid,” says Paul Ashby, a Molecular Foundry staff scientist who led this research in the Foundry’s Imaging and Manipulation of Nanostructures Facility. “If we have an investigative probe that excels in this environment, we could image individual proteins as they function on the cell surface.”

Says Babak Sanii, a post-doctoral researcher in the Foundry, “Shrinking the cantilever down to nanoscale dimensions dramatically reduces the force it applies, but to monitor the movements of such a small cantilever, we needed a new detection scheme.”

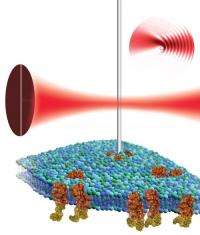

Rather than measuring the cantilever’s deflection by bouncing a laser off it, Ashby and Sanii place the nanowire cantilever in the focus of a laser beam and detect the resulting light pattern, pinpointing the nanowire’s position with high resolution. The duo say this work provides a launching pad for building a nanowire-based atomic force microscopes that could be used to study biological cells and model cellular components such as vesicles or bilayers. In particular, Ashby and Sanii hope to learn more about integrins, proteins found on the surface of cells that mediate adhesion and are part of signaling pathways linked to cell growth and migration.

“No present technique probes the assembly and dynamics of protein complexes in the cell membrane,” adds Ashby. “A dynamic probe is the holy grail of soft matter imaging, and would help determine how protein complexes associate and disassociate.”

“High sensitivity deflection detection of nanowires,” by Babak Sanii and Paul D. Ashby, appears in Physical Review Letters.

Provided by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory