Oil's hidden costs visible, but will it matter?

(AP) -- America is seeing the usually hidden costs of fossil fuels - an oil spill's potential for huge environmental and economic damage, and deaths in coal and oil industry accidents.

But don't expect much to change. America and the world crave more oil and coal, no matter the all-too-risky ways needed to extract those fuels.

"We are absolutely addicted and we have no methadone. All we have is the hard stuff," said Larry McKinney, director of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M University Corpus Christi. "The reality is we're on it, this incident has happened and what we have to do is figure out how we can move forward."

The United States is increasing its dependence on oil and other fossil fuels. And more domestic oil has to come from offshore because the land is producing less. The alternatives of renewable energy aren't cheap and aren't progressing quickly despite three decades of energy crises and legislation.

Oil industry officials, such as former Shell Oil Co. President John Hofmeister, see the well blowout in the Gulf of Mexico as defeat being snatched from the jaws of victory. A Democratic president had just opened up to drilling areas of U.S. coastline that once seemed untouchable. "Drill baby drill" has been replaced with the phrase, "Whoa, there."

Myron Ebell of the conservative Competitive Enterprise Institute, which usually rails against too much government intervention into business, spoke Tuesday of the need for "more scrutiny of the industry" and regulations. That way drilling can continue.

BP's leaking well off the coast of Louisiana is that much of a game changer - at least in the way people talk.

Environmental activists see this as a moment when the public pushes aside an industry - like the Three Mile Island nuclear plant's partial meltdown did to nuclear energy.

"The thing that we had hoped would never happen has just happened," said Anna Aurilio, Washington office director for Environment America. "I think this has potential to really reset the conversation of climate and energy."

Likewise President Barack Obama's White House sees this as coinciding with the $80 billion in stimulus money already spent and going partly toward moving America's effort away from fossil fuels to a greener energy economy.

"We need a new energy plan for this country ... that begins a transition to renewable and battery technology," White House energy and climate change senior adviser Carol Browner told The Associated Press Tuesday. "We can push and have been pushing for legislation that will begin the change."

An odd but understandably muted tone has been adopted by both oil interests and many environmentalists. Aurilio had a hitch in her voice as she said: "Quite frankly, we're heartbroken. This disaster is touching us personally. This is something to pray that will never happen again."

Here in Houston, capital of the American oil industry, those at an offshore drilling technology conference don't like to say it too much or publicly - but no one is too worried about a public turning its back on oil and coal.

Why? They know there is not much of an alternative.

"There will be a temptation in that direction. When you see the risks of hydrocarbons you have to ask yourself, is this as good as it gets?" former Shell president Hofmeister told The Associated Press. "The good news is that hydrocarbon for all of its risks - meaning coal, gas and oil - is much less risky today than it was earlier in the industry's history."

Hofmeister, author of the new book "Why We Hate the Oil Companies," said that America not only has to keep drilling for more oil in places like the Gulf of Mexico, but increase its drilling.

By 2020 if drilling is limited, he said: "We will be in a new age in this country. It will be called the age of the energy abyss."

Hofmeister said no industry is hated more than the oil industry - it polls even lower than the federal government - but until the internal combustion engine is replaced, people will demand more oil. Especially when gas prices hit $4 a gallon - something Browner said can't be blamed on the oil spill since the well was an exploratory one, not one already supplying fuel.

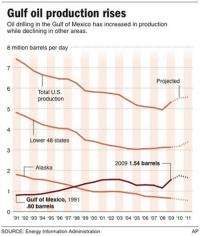

"More and more of our oil and gas has to come from offshore. All you have to do is look at the historical trend," said Tyler Priest, an oil historian at the University of Houston.

Since 1991, oil production on U.S. land and in Alaska has dropped 40 percent, but it has nearly doubled in the Gulf of Mexico, according to federal statistics.

A 2008 International Energy Agency report estimates that reachable conventional oil located in water more than a quarter-mile deep is between 160 and 300 billion barrels, with more than two-thirds of that in Brazil, Angola, Nigeria and the United States.

"Our energy security is going to hang on whether we can drill offshore," said Amy Myers Jaffe, an energy studies fellow at Rice University's public policy institute.

So what are the costs?

It starts with the possibly devastating oil spill unfolding right now off the coast of Louisiana.

McKinney's research institute in Corpus Christi estimated a worst-case scenario cost of the spill to the Gulf of Mexico: $1.6 billion.

About one-quarter of that is due to lost fishing and tourism. But the bulk of the cost is in the stuff that's less easy to quantify: the general wetlands ecology. If half a million acres of wetlands are severely damaged, that drastically affects a fragile area that acts as a wastewater treatment plant for water flowing out of the Mississippi River - where 40 percent of America's water flows into. And every acre of wetland means one less foot of storm surge from a hurricane, he said.

McKinney worries that this is "strike three" for the Gulf's wetlands. First, they've been shrinking because of development and engineering changes to natural drainage in Louisiana. Then Hurricane Katrina damaged them. And now this.

"This one is getting all of us worried," McKinney said.

But that's not all, environmentalists point out. There are lives lost in getting oil and coal.

Another coal miner died in an accident Tuesday in West Virginia, that's in addition to the 29 who died in a massive explosion April 5 in that state and an accident last week that killed two in Kentucky. Besides the accidents, more than 29,000 workers have died of coal mining-related lung diseases since 1968, according to the federal government.

The BP PLC oil rig explosion April 20 that caused the spill also claimed 11 lives. That came only weeks after an April 2 refinery fire in Washington state that killed seven workers. In 2008, work accidents killed 120 people in the oil and gas extraction industry, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

Add to that global warming. Burning oil and coal produces carbon dioxide, which scientists say is changing the Earth's climate and will eventually change the life of nearly everyone on the planet.

This year, after what seemed like a cool winter in some spots, the heat is back on. Already it's shaping up to be one of the warmest on record, with a record-setting March, according to both government weather statistics and those kept by global warming skeptics at the University of Alabama Huntsville.

"What we're seeing is proof positive of our dependence of oil and gas and we've ignored that in the past," McKinney said. "Unfortunately it's being rubbed in our face right now."

©2010 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.