Recreating Venus in the Lab

Scientists are reproducing the environment of Venus so that they can interpret observations of the planet's surface and atmosphere. Studying environmental processes on Venus can help astrobiologists better understand the climate systems of Earth and the habitability of rocky planets.

Scientists are able to learn about the atmospheres and surfaces of planets by studying their spectra - the different wavelengths of light which they reflect or absorb. However, when researchers study spectra of Venus, the hottest planet in the solar system, they run into a problem. Its high temperatures and pressures seriously affect the data.

Venus and Earth are often described as sister worlds. However, the second planet from the Sun has obviously evolved in a very different manner from our Earth. The surface of Venus is very hot, with temperatures reaching 480 degrees Celsius, and its surface pressure is 90 times greater than on Earth. These extreme conditions cause great difficulties for scientists who are attempting to unveil the mysteries of the Venusian lower atmosphere and surface.

"Remote observation of the surface and atmosphere, particularly at infrared wavelengths, enables us to probe the deepest regions of the atmosphere and surface of Venus," explained Hakan Svedhem, Venus Express Project Scientist.

"On Earth, we understand the spectral absorption lines in the atmosphere, so we can calculate their effects. However, the high temperatures and pressures on Venus make observations much more complex. We don't know precisely how they modify the spectra, so it is impossible to interpret the data accurately."

In an effort to overcome this problem of interpretation, teams of scientists in several countries are attempting to reproduce the extreme environment of Venus and discover how it affects the data sent back by instruments such as the Visible InfraRed Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS) onboard ESA's Venus Express orbiter.

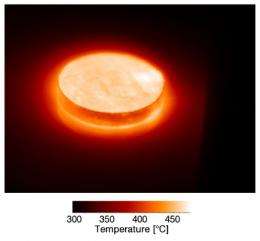

In the Planetary Emissivity Laboratory in Berlin, Joern Helbert and colleagues are trying to find out by heating rock and dust samples to 500 °C. As their temperatures rise, the samples start to glow, first in the infrared and then in the visible. Since the relative strength of this glow at different wavelengths - its emissivity - is unique to each material, it can be used to identify rocks on the planet's surface.

"High temperatures change the internal structure of minerals, so that some become brighter and others are darker," said Helbert. "We have been working on this problem for three years, using a unique apparatus in which we heat samples in stainless steel cups with an induction heating system. This enables us to go very quickly to high temperatures and keep the temperature very stable. We are now starting to make real measurements of basalt, haematite and granite in the lab, so that we can compare them with emissivity data from VIRTIS."

Using these new lab measurements, Helbert's team hopes to unravel the mineralogy and history of Venus' surface, including the apparent resurfacing of the planet by vast outflows of lava during the last one billion years.

Understanding the properties of the carbon-dioxide-enriched atmosphere presents another major challenge. The lower atmosphere of Venus is like an extreme pressure cooker which is twice as hot as a domestic oven. All light from the surface must pass through this dense, overheated atmosphere before reaching the instruments on Venus Express.

The carbon dioxide blocks most infrared light coming from the surface, but the optical properties of the gas are not fully understood, especially at wavelengths where the gas is almost "transparent". Scientists want to understand how the atmosphere absorbs light from below, and to define accurately the spectral windows which give the clearest views of the lower atmosphere and surface. Only then will they be able to comprehend the finest details of the spectrum and unravel the nature of the planet hidden beneath its blanket of cloud and thick greenhouse gas.

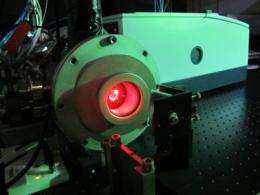

To fill this gap in knowledge, a team led by Giuseppe Piccioni, Principal Investigator for the VIRTIS instrument, is trying to reproduce Venus' atmospheric conditions in the lab. Their research at IASF-Rome of the National Institute for Astrophysics, Italy, involves studying carbon dioxide spectra at temperatures and pressures similar to those on Venus.

"We use tiny sample cells filled with carbon dioxide, which have to be carefully constructed to withstand the extreme conditions," said Piccioni. "We then use very high resolution spectrometers in order to get precise measurements of the light absorption by the gas."

The painstaking lab work is ongoing, but once the relatively clear spectral windows are clearly defined and recognised, it will be possible to produce accurate, three-dimensional models of the distribution of atmospheric temperatures and gases in the lower atmosphere.

This breakthrough will open the door to detailed analysis of the dynamics and composition of the atmosphere, including the mysterious four-day wind circulation, the polar vortices, and the distribution of water and other minor constituents.

Papers on both of these research activities were presented at the COSPAR conference in Bremen, Germany, 18-25 July 2010.

Provided by European Space Agency