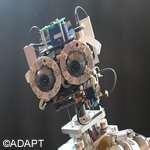

BabyBot takes first steps

BabyBot, a robot modelled on the torso of a two year-old child, is helping researchers take the first, tottering steps towards understanding human perception, and could lead to the development of machines that can perceive and interact with their environment.

The researchers used BabyBot to test a model of the human sense of 'presence', a combination of senses like sight, hearing and touch. The work could have enormous applications in robotics, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine perception. The research is being funded under the European Commission’s FET (Future and Emerging Technologies) initiative of the IST programme, as part of the ADAPT project.

"Our sense of presence is essentially our consciousness," says Giorgio Metta, Assistant Professor at the Laboratory for Integrated Advanced Robotics at Italy's Genoa University and ADAPT project coordinator.

Imagine a glorious day lying on a beach, drinking a pina colada, or any powerful, pleasurable memory. A series of specific sensory inputs are essential to the memory.

In the human mind all these sensations combine powerfully to create the total experience. It profoundly influences our future expectations, and each time we go to a beach we add to the store of contexts, situations and conditions. It is the combination of all these inputs and their cumulative power that the ADAPT researchers sought to explore.

Engineering consciousness

"We took an engineering approach to the problem, it was really consciousness for engineers," says Metta, "Which means we first developed a model and then we sought to test this model by, in this case, developing a robot to conform to it."

Modelling, or defining, consciousness remains one of the intractable problems of both science and philosophy. "The problem is duality, where does the brain end and the mind begin, the question is whether we need to consider them as two different aspects of reality," says Metta.

Neuroscientists would tend to develop theories that fit the observed phenomena, but engineers take a practical approach. Their objective is to make it work.

Called the synthetic methodology, it is essentially a method of understanding by building. There are three steps: model aspects of a biological system; abstract general principles of intelligent behaviour from the model; apply these principles to the design of intelligent robots. Model, test, refine. And then repeat.

To that end, ADAPT first studied how the perception of self in the environment emerges during the early stages of human development. So developmental psychologists tested 6 to 18 month-old infants. "We could control a lot of the parameters to see how young children perceive and interact with the world around them. What they do when interacting with their mothers or strangers, what they see, the objects they interact with, for example," says Metta.

From this work they developed a 'process' model of consciousness. This assumes that objects in the environment are not real physical objects as such; rather they are part of a process of perception.

The practical upshot is that, while other models describe consciousness as perception, cognition then action, the ADAPT model sees it as action, cognition then perception. And it's how babies act, too.

When a baby sees an object that is not the final perception of it. A young child will then try to reach the object. If the child fails, the object is too far away. This teaches the child perspective.

If the child does reach the object, he or she will try to grasp it, or taste it or shake it. These actions all teach the child about the object and govern its perception of it. It is a cumulative process rather than a single act.

Our expectations also have enormous influence on our perception. For example, if you believe an empty pot is full, you will lift the pot very quickly. Your muscles unconsciously prepare for the expected resistance, and put more force than is required into lifting; everyday proof that our expectations govern our relationship with the environment.

Or at least that's the model. "It's not validated. It's a starting point to understand the problem," says Metta.

From model to BabyBot

The team used BabyBot to test it, providing a minimal set of instructions, just enough for BabyBot to act on the environment. For the senses, the team used sound, vision and touch, and focused on simple objects within the environment.

There were two experiments, one where BabyBot could touch an object and second one where it could grasp the object. This is more difficult than it sounds. If you look at a scene, you unconsciously segment the scene into separate elements.

This is a highly developed skill, but by simply interacting with the environment the BabyBot did its engineering parents proud when it demonstrated that it could learn to successfully separate objects from the background.

Once the visual scene was segmented, the robot could start learning about specific properties of objects useful, for instance, to grasp them. Grasping opens a wider world to the robot and to young infants too.

The work was successful, but it was a very early proof-of-principle for their approach. The sense of presence, or consciousness, is a huge problem and ADAPT did not seek to solve it in one project. They made a very promising start and many of the partners will take part in a new IST project, called ROBOTCUB.

In ROBOTCUB the engineers will refine their robot so that it can see, hear and touch its environment. Eventually it will be able to crawl, too.

"Ultimately, this work will have a huge range of applications, from virtual reality, robotics and AI, to psychology and the development of robots as tools for neuro-scientific research," concludes Metta.

Source: IST Results