New process generates hydrogen from aluminum alloy to run engines, fuel cells

A Purdue University engineer has developed a method that uses an aluminum alloy to extract hydrogen from water for running fuel cells or internal combustion engines, and the technique could be used to replace gasoline.

The method makes it unnecessary to store or transport hydrogen - two major challenges in creating a hydrogen economy, said Jerry Woodall, a distinguished professor of electrical and computer engineering at Purdue who invented the process.

"The hydrogen is generated on demand, so you only produce as much as you need when you need it," said Woodall, who presented research findings detailing how the system works during a recent energy symposium at Purdue.

The technology could be used to drive small internal combustion engines in various applications, including portable emergency generators, lawn mowers and chain saws. The process could, in theory, also be used to replace gasoline for cars and trucks, he said.

Hydrogen is generated spontaneously when water is added to pellets of the alloy, which is made of aluminum and a metal called gallium. The researchers have shown how hydrogen is produced when water is added to a small tank containing the pellets. Hydrogen produced in such a system could be fed directly to an engine, such as those on lawn mowers.

"When water is added to the pellets, the aluminum in the solid alloy reacts because it has a strong attraction to the oxygen in the water," Woodall said.

This reaction splits the oxygen and hydrogen contained in water, releasing hydrogen in the process.

The gallium is critical to the process because it hinders the formation of a skin normally created on aluminum's surface after oxidation. This skin usually prevents oxygen from reacting with aluminum, acting as a barrier. Preventing the skin's formation allows the reaction to continue until all of the aluminum is used.

The Purdue Research Foundation holds title to the primary patent, which has been filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and is pending. An Indiana startup company, AlGalCo LLC., has received a license for the exclusive right to commercialize the process.

The research has been supported by the Energy Center at Purdue's Discovery Park, the university's hub for interdisciplinary research.

"This is exactly the kind of project that suits Discovery Park. It's exciting science that has great potential to be commercialized," said Jay Gore, associate dean of engineering for research, the Energy Center's interim director and the Vincent P. Reilly Professor of Mechanical Engineering.

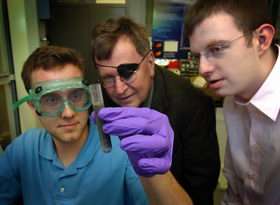

The research team is made up of electrical, mechanical, chemical and aeronautical engineers, including doctoral students.

Woodall discovered that liquid alloys of aluminum and gallium spontaneously produce hydrogen if mixed with water while he was working as a researcher in the semiconductor industry in 1967. The research, which focused on developing new semiconductors for computers and electronics, led to advances in optical-fiber communications and light-emitting diodes, making them practical for everything from DVD players to automotive dashboard displays. That work also led to development of advanced transistors for cell phones and components in solar cells powering space modules like those used on the Mars rover, earning Woodall the 2001 National Medal of Technology from President George W. Bush.

"I was cleaning a crucible containing liquid alloys of gallium and aluminum," Woodall said. "When I added water to this alloy - talk about a discovery - there was a violent poof. I went to my office and worked out the reaction in a couple of hours to figure out what had happened. When aluminum atoms in the liquid alloy come into contact with water, they react, splitting the water and producing hydrogen and aluminum oxide.

"Gallium is critical because it melts at low temperature and readily dissolves aluminum, and it renders the aluminum in the solid pellets reactive with water. This was a totally surprising discovery, since it is well known that pure solid aluminum does not readily react with water."

The waste products are gallium and aluminum oxide, also called alumina. Combusting hydrogen in an engine produces only water as waste.

"No toxic fumes are produced," Woodall said. "It's important to note that the gallium doesn't react, so it doesn't get used up and can be recycled over and over again. The reason this is so important is because gallium is currently a lot more expensive than aluminum. Hopefully, if this process is widely adopted, the gallium industry will respond by producing large quantities of the low-grade gallium required for our process. Currently, nearly all gallium is of high purity and used almost exclusively by the semiconductor industry."

Woodall said that because the technology makes it possible to use hydrogen instead of gasoline to run internal combustion engines it could be used for cars and trucks. In order for the technology to be economically competitive with gasoline, however, the cost of recycling aluminum oxide must be reduced, he said.

"Right now it costs more than $1 a pound to buy aluminum, and, at that price, you can't deliver a product at the equivalent of $3 per gallon of gasoline," Woodall said.

However, the cost of aluminum could be reduced by recycling it from the alumina using a process called fused salt electrolysis. The aluminum could be produced at competitive prices if the recycling process were carried out with electricity generated by a nuclear power plant or windmills. Because the electricity would not need to be distributed on the power grid, it would be less costly than power produced by plants connected to the grid, and the generators could be located in remote locations, which would be particularly important for a nuclear reactor to ease political and social concerns, Woodall said.

"The cost of making on-site electricity is much lower if you don't have to distribute it," Woodall said.

The approach could enable the United States to replace gasoline for transportation purposes, reducing pollution and the nation's dependence on foreign oil. If hydrogen fuel cells are perfected for cars and trucks in the future, the same hydrogen-producing method could be used to power them, he said.

"We call this the aluminum-enabling hydrogen economy," Woodall said. "It's a simple matter to convert ordinary internal combustion engines to run on hydrogen. All you have to do is replace the gasoline fuel injector with a hydrogen injector."

Even at the current cost of aluminum, however, the method would be economically competitive with gasoline if the hydrogen were used to run future fuel cells.

"Using pure hydrogen, fuel cell systems run at an overall efficiency of 75 percent, compared to 40 percent using hydrogen extracted from fossil fuels and with 25 percent for internal combustion engines," Woodall said. "Therefore, when and if fuel cells become economically viable, our method would compete with gasoline at $3 per gallon even if aluminum costs more than a dollar per pound."

The hydrogen-generating technology paired with advanced fuel cells also represents a potential future method for replacing lead-acid batteries in applications such as golf carts, electric wheel chairs and hybrid cars, he said.

The technology underscores aluminum's value for energy production.

"Most people don't realize how energy intensive aluminum is," Woodall said. "For every pound of aluminum you get more than two kilowatt hours of energy in the form of hydrogen combustion and more than two kilowatt hours of heat from the reaction of aluminum with water. A midsize car with a full tank of aluminum-gallium pellets, which amounts to about 350 pounds of aluminum, could take a 350-mile trip and it would cost $60, assuming the alumina is converted back to aluminum on-site at a nuclear power plant.

"How does this compare with conventional technology? Well, if I put gasoline in a tank, I get six kilowatt hours per pound, or about two and a half times the energy than I get for a pound of aluminum. So I need about two and a half times the weight of aluminum to get the same energy output, but I eliminate gasoline entirely, and I am using a resource that is cheap and abundant in the United States. If only the energy of the generated hydrogen is used, then the aluminum-gallium alloy would require about the same space as a tank of gasoline, so no extra room would be needed, and the added weight would be the equivalent of an extra passenger, albeit a pretty large extra passenger."

The concept could eliminate major hurdles related to developing a hydrogen economy. Replacing gasoline with hydrogen for transportation purposes would require the production of huge quantities of hydrogen, and the hydrogen gas would then have to be transported to filling stations. Transporting hydrogen is expensive because it is a "non-ideal gas," meaning storage tanks contain less hydrogen than other gases.

"If I can economically make hydrogen on demand, however, I don't have to store and transport it, which solves a significant problem," Woodall said.

Source: Purdue University